What is a Steamed Dumpling?

A steamed dumpling is a delicious Chinese snack that can be eaten hot or cold. It’s usually made from wheat flour, water, and sometimes eggs. The mixture is rolled into little balls and then steamed in a bamboo basket for about 20 minutes.

You can buy steamed dumplings at any Chinese grocery store or fresh market. They’re also easy to make at home!

Tibetan Origin of Dumplings

The momo is the quintessential Tibetan treat enjoyed enthusiastically in Tibet and across the world since the Tibetan diaspora. As a treat stuffed with yak or cow meat, its popularity presents a peculiar paradox considering most Tibetans practice buddhism and adhere to a vegetarian diet.

Something profound pulls at the heartstrings of the Tibetans who crave these steamed pockets of satisfaction. What ever could it be?

MOMOS: THE DALAI LAMA, DELECTABLE DUMPLINGS, AND BOS GRUNNIENS

If the momo is the quintessential Tibetan dish, His Holiness the Dalai Lama is the quintessential Tibetan figure. You can hardly think of Tibet without immediately picturing his kind face and enlightened teachings.

The Dalai Lama embodies the somewhat confusing partial-vegetarianism of Tibetan buddhists. As he so often does, let’s have him inform our world view as we delve into the cuisine of his people.

DUMPLINGS VS. POTSTICKERS

Steamed dumplings and potstickers are both delicious, but they have some key differences.

Steamed dumplings are made with a dough that’s wrapped around a filling, whereas potstickers are made with a thin dough that is sealed around a filling. Steamed dumplings are also typically stuffed with ground meat and veggies, while potstickers can contain just about anything—meat, seafood, veggies… even cheese!

The main difference between these two delicious treats is their cooking method: steamed dumplings are steamed in the oven or on the stovetop, while potstickers are pan-fried.

You May Also Like…

If you like dumplings, you might want to check out our other recipe for Slovakian Potato Dumplings, or Mongolian Meat Dumplings (Buuz), or Siberian Meat Dumpling (Pelmeni)

DUMPLINGS VS. WONTONS

Steamed dumplings and wontons are both delicious, but they’re different in a few ways.

Steamed dumplings are usually eaten as part of a meal, while wontons can be eaten as an appetizer or as a main dish. Steamed dumplings are usually filled with meat or vegetables, while wontons are usually filled with meat and sometimes vegetables.

Steamed dumplings are made by wrapping dough around various fillings and then steaming them until they’re cooked through. Wonton wrappers also surround fillings, but they’re fried instead of steamed—and after frying, they’re often served in broth or soup.

DUMPLINGS VS. GYOZA

Steamed dumplings and gyoza are both Asian dumplings, but they have a few differences.

Gyoza are made with a thinner wrapper than steamed dumplings, so they’re usually more delicate. They’re also smaller, which makes them easier to eat in one bite. Steamed dumplings are usually cooked in a bamboo steamer, while gyoza are cooked on a flat pan or skillet.

Both types of dumplings are great for eating at home or bringing to a party—you can make either type very quickly and easily!

TENZIN GYATSO: THE FOURTEENTH DALAI LAMA

In a small farming hamlet in eastern Tibet in 1935, a boy named Lhamo Dhondup was born. Two years later, a group of monks ventured to this relative lowland in Tibet 9,000 feet above sea level and concluded the boy was the reincarnation of the previous Dalai Lama.

Little Lhamo and his family journeyed to Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, in 1939. The young boy would become the Dalai Lama, the spiritual and political leader of Tibet, and his name would be changed to Tenzin Gyatso.

When China invaded Tibet in 1959, the Dalai Lama, like countless other Tibetans, fled the country. He left behind him many of the people who worked and lived at the palace where he resided in Lhasa.

One such man who stayed behind was a monk named Gyaltsen Phensok, whose chief responsibility was ensuring that His Holiness imbibed only the finest yak milk and yogurt. Incredibly, this responsibility was a shared responsibility. That must have been some phenomenal yogurt!

During an interview with this yak dairy savant, it was unclear as to whether or not the Dalai Lama ate momos, but the Internet is positively brimming with a recipe for the dumplings that supposedly are from Tenzin Gyatso himself.

Since the Dalai Lama’s escape from Tibet in the 1950s, he has resided in India, and at his palace in Dharamhsala, it is officially a vegetarian-only kitchen. However, the Dalai Lama does eat meat when not at the palace, and apparently it’s for health reasons. Meat has been part of the Tibetan diet for generations, where the harsh mountain life demanded nutrient dense food in order to survive.

Meat Dumpling with Butter

You might be also be interested in this boiled Meat Dumpling recipe served with delicious melted butter!

JIAOZI BEGETS MOMOS, RIGHT?

In the now familiar song of recipes who date back hundreds or even thousands of years, it’s unclear exactly how momos came to be. Two main theories tear at the very fiber of would be “dumpling scholars.”

Did they enter Tibet from China, who enjoyed very similar jiaozi in their cuisine? This is one very real possibility. In Chinese, momo literally means “steamed bread.” Although, we were unable to make the connection between the name jiaozi and momo. Adherents to the jiaozi theory believe that dumplings came into Tibet with traders and travelers, and upon arrival, they were adapted and stuffed with the Tibetan meat of choice, yak.

Those who shun this theory posit their own. Did these piquant pouches actually originate in Tibet itself? Some believe that the Newari people of the Kathmandu valley (whom we saw with chatamari too) created them. These believers say that the Newari people brought the dumplings into Tibet, and that the dish is actually of Nepali origin… neither Tibetan nor Chinese.

We know better than to get in the middle of the “who created this recipe” battle. The memory of the waring towns in Nicaragua who claim creation of the quesillo is fresh in our minds, so we will leave the theories at peace and explore just what exactly these Tibetans like stuffing their dumplings with so much.

YAK-ETY YAK, DON’T TALK BACK

The most traditional, if we may be so bold as to qualify tradition, filling for momos is yak meat. In Tibet, yak meat is the most popular filling because it was traditionally the most available.

Perhaps you are asking yourself, why a Buddhist who normally shies away from meat would eat yak in the first place? It seems contrary to the common practice of avoiding meat for moral reasons, but when needing meat for sustenance, the “karmic load” of killing one yak is equal to killing a chicken or a rabbit. All else being equal, more people can be fed by the death of a yak than by the death of a smaller animal.

But why are yak so central to Tibetan life and cuisine? It’s not because of the song “Yakety Yak” by the Coasters soared to such popularity in Tibet in 1986.

In fact, yak, or bos grunniens if you prefer their scientific name, have been running wild throughout modern day Tibet for about 2.5 million years before they were domesticated. Yak are an incredible animal capable of surviving the harsh mountainous terrain and frigid temperatures in Tibet and are well-suited to survive at elevations of up to 5,000 meters!

It was roughly 10,000 years ago that they were first domesticated in the “roof of the world.” In Tibet, yaks are not only raised for meat, but their milk is also used for butters and cheeses. Their strong bodies pull plows and wagons, and they are even ridden in yak races!

These large, extra furry bovines are actually believed to be more closely related to bison than to cows. Although the evidence of this is scant, if you take one look at a yak it seems clear that they are more than just cousins to the burly bisons. If you are thinking of going 100% authentic with your momo recipe, then we strongly suggest you find a butcher with a hefty cut of yak meat.

If you don’t think there is a yak butcher nearby, fear not, the Tibetan diaspora has adapted the ingredients to make the shopping list a bit more friendly.

ABOUT THE RECIPE

Yes, technically there’s the traditional sha momo made with minced beef – or even more traditionally, minced yak – but nowadays the momo has come to take on all sorts of filling options. As you’ll see in our version of the recipe, preparing a traditional sha dumpling is as fine as preparing a vegetarian-only option.

The filling is actually the easy part of the entire momo creation process. You’ll take all your ingredients for your preferred filling and put it into the food processor. Blitz and process everything until you have very finely chopped pieces that can nestle nicely in between the skin of your dumpling. You don’t necessarily want to puree your filling ingredients, but you don’t want such large pieces that they protrude and break the dumpling skin either.

HOW TO MAKE DUMPLINGS

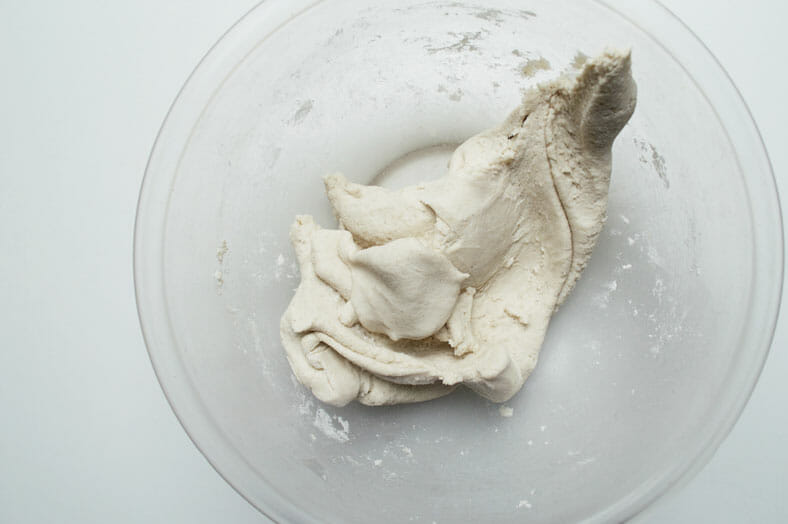

As for the momo dough, you want to create a thicker, heartier type of dumpling skin somewhat akin to what we saw with Mongolian buuz. Take your wheat flour and mix enough water in with it to create a dough that’s somewhat elastic, but it should still feel slightly dry to the touch. As long as you can roll it out on a flat floured surface to ~1/3 inch thickness, you’re on the right track. And don’t worry about the moisture… it will get plenty while it’s steaming!

Just like it’s very easy to prepare the filling with the food processor, it’s very easy to prepare right-sized momo with a circular pastry cutter. Simply roll and flatten your dough until the right thickness, then cut out as many uniform sized pieces from your sheet as you can.

To finish the process, take on circle of dough in your hand and plop in a tablespoon of your preferred filling. Fold one side of dough over towards the other, and very tightly pinch your way along the dough line until you’ve enclosed the filling on the inside. Repeat until you have enough to fill a steamer tray for your first batch.

STEAMING

Our Favorite Bamboo Dumplings Steamer

For steaming, in case you don’t have a bamboo steamer basket – though they’re very inexpensive and relatively easy to procure, especially at Asian supermarkets – one option you have is to take a wide saucepan with a lid and line it with ~1/2 inch of water. On top of the water, you’re going to place a steamer tray to help keep your momos safe from direct contact with the water.

Bring your water to a boil, and while doing so, lightly oil your steaming tray. One trick you might want to also try – which is also a great way to protect from direct water contact – is to line the steamer tray with either parchment paper or banana leaf or anything that can withstand the heat from the steam. When the water is boiling, reduce your stovetop heat to a simmer, place your steamer tray in, add your prepared set of momos and let it all steam together.

A momo should only take about 12-15 minutes to steam depending on the thickness of your dough. Check periodically towards the end to see how it’s doing. If it’s still slightly moist to the touch, it has some ways to go, but if it feels dry, then it is fully cooked and done.

CHUTNEYS: ACHAR OR SEPEN

One thing’s for certain: Tibetans love their momos with a dipping sauce. Two very common options involve achar, a tomato-based sauce that’s equally loved by Nepalis, and sepen, an intensely hot sauce made from bird’s eye chilis and soy sauce.

In our case, we chose to go with achar for our own recipe, but the premise for making both chutneys is the same. Heat up and cook down your ingredients in a saucepan until well-mixed and relatively soft, then blend it down to your desired consistency and thickness.

Serve it alongside your momo, and enjoy!

OUR TAKE ON THE RECIPE

From start to finish, there were a few good options for reference recipes, but we found one that covered the dough, the filling and the chutney, which is why we chose it as our original source. Nevertheless, we made some changes both to ingredients and to procedure.

For starters, we made our momo dough less heavy on the all-purpose flour and more evenly balanced between all-purpose and whole wheat. Since it’s renowned as a wheat dumpling, we felt it was okay to add more wheat to the flour itself.

When creating the filling, we made the process easier by using a food processor versus manually chopping. Between that and using a pastry cutter to create uniform-sized momo, we were able to cut down the overall cooking process by roughly half.

Finally, we more generally made the switch away from vegetable oil to healthier oils like olive. Another key addition we made as well was to make abundant and generous use of chopped spring onion, which we thought made everything better.

Otherwise, it’s very much up to you how you’d like to shape and mold your own momo. It’s a fantastically flexible and versatile dish, and especially with a chutney in tow, it makes for a fun and memorable meal.

Enjoy!

How would you fill your momo? Comment below!