Qurutob is the embodiment of the treacherous topography and fascinating history of Tajikistan. The Tajik people live in an extreme climate and have recently endured decades of domestic challenges.

At the center of an ancient road that united cultures across many continents lie the Pamir Mountains in eastern Tajikistan. Nestled in the high mountains of Central Asia, the Tajik people have developed a cuisine that is truly food in its purest form.

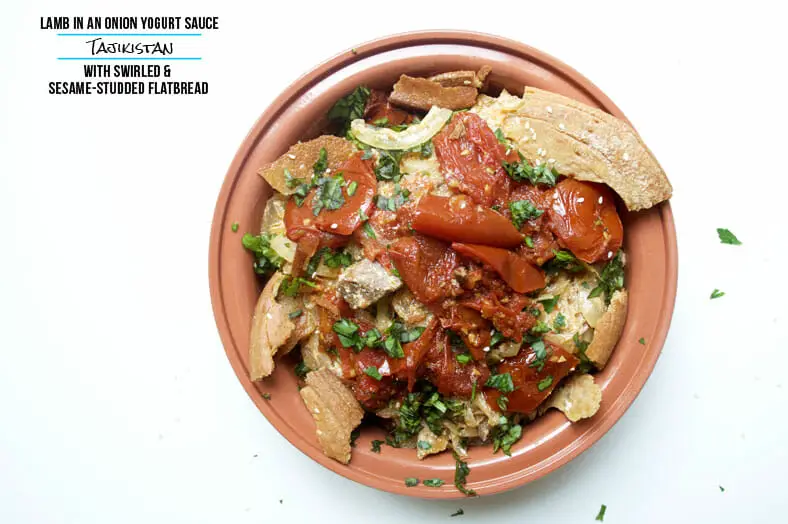

QURUTOB: THE PAMIR MOUNTAINS, MARCO POLO AND TAJIK TENACITY

Tajikistan is mostly a desert, but not the desert you might be imagining with vast swaths of sand dotted with the occasional camel. It is a bitterly cold desert, with snow capped mountains and herds of yaks.

The Pamir mountain range makes up most of Tajikistan. These lofty mountains are covered in snow year round and see little precipitation. Long, cold winters, and short, cool summers dominate life in Tajikistan.

THE ROOF OF THE WORLD: THE PAMIR MOUNTAINS

The Pamir mountain range lies at the center of the world’s highest mountain ranges. From the Pamir mountains, the Himalayas, the Karakoram, the Hindu Kush, and the Tian Shen mountains radiate to the East, West, and South, their towering peaks stretching high into the heavens.

The tallest mountain in the Pamir range is Kongur Tagh, at a mighty 7,649 meters, or 25,095 feet. This lands Kongur Tagh at number 37 on the list of world’s tallest mountains, some 1,200 meters (or 4,000 feet) shy of Mount Everest. But don’t scoff at this high thirties ranking, the Pamirs, and their central Asian cousins, tower over the mountains on every other continent.

Seated in these mountains are glaciers, valleys and flat lands, is a topography that has lent itself to exploration and travel for thousands of years, but we’ll let Sir Marco Polo tell us more about that later.

Incredibly, the ancestors of the Tajik people have been living among these mountains since the Bronze Age. There is archeological evidence of human habitation in the Pamir mountains as far back as the Mesolithic era, roughly 8,500 BCE, but then the record takes a several thousand year break until the Bronze Age.

Persian geographers referred to the Pamir mountains as Bam i Dúniah, which means the Roof of the World. The great plain of Bam i Dúniah is 15,800 feet high, which is as high as the peak of Mont Blanc.

And it is here, in the roof of the world, where qurutob is made. It is also eaten in the capital city of Tajikistan, Dushanbe, which is not in the Pamir mountains. Still, it’s more fun to imagine the Tajiks who eat qurutob with their families in a yurt thousands of feet above us.

You Might Also Like…

If you love lamb you might want to check out our other recipe on an Albanian lamb with yogurt casserole (tave kosi), or a slow cooked gluten free lamb stew from Pakistan (nihari).

If you just love this type of yogurt sauce, you might enjoy our other recipe on a braised beef loin with sour cream sauce from Austria.

MARCO POLO AND THE SILK ROAD

The Silk Road is a network of ancient trade routes that flowed out of China and across Asia to Europe, Africa and India. Traders used the Silk Road from the second century BCE to the fifteenth century CE to transport all manner of goods.

The Pamir Mountains lie along the northern route of the Silk Road. One of the most famous objects to travel out of the Pamir Mountains and along the Silk Road was a 170 carat ruby now snuggly mounted in the Imperial State Crown of Britain.

Many famous explorers journeyed along the Silk Road, but its most famous traveller is perhaps Marco Polo.

Long before he became a household name children scream while splashing around in pools with their eyes closed, Marco Polo was the son of a Venetian merchant who accompanied his father on a voyage along the Silk Road.

He would continue his worldly exploration on his own, setting off on a journey from Venice to Karakoram. Along the way, he wrote of his travels, leaving behind a vivid picture of what the world was like in the 13th and 14th centuries. This journey took him along the Silk Road, and through none other than the Pamir mountains.

It took Marco Polo and his companions twelve days to cross the plain of the Pamir mountains. According to him, the plain was so high that not even birds flew there. There were no settlements or shelter along the way, and it was bitterly cold.

Fortunately, Marco made it through the plain and arrived at Karakoram, the seat of the Mongol Empire, and he went on to live the rest of a fascinating life.

TAJIKISTANI TENACITY

The people of Central Asia, who live among the tallest mountains on earth, are some of the hardiest humans. Make no mistake about it: living at the Bam i Dúniah requires grit and strength.

If the harsh climate and topography of Tajikistan did not pose enough challenges for the Tajik, conquest from outsiders and internal conflict have created additional hardships for her people.

Tajikistan was first conquered by the Mongol Empire in the 13th century. After the fall of the Empire the Tajik, people were ruled by the Timurid and later the Turkic dynasty until the 19th century, when Tajikistan was divided in two by the Russian Tsar and the Emirate of Bukhara. Tajikistan would be unified again by the USSR in the 20th century, only to plunge into civil war once the Soviet Union broke apart.

Although Tajikistan is the poorest country in the former Soviet sphere, and one of the poorest in the world, the Tajik people define happiness on their own terms. Those who live in the Pamir mountains are generous, inviting and hopeful.

If home is a mountain plain higher than even an eagle might soar, and winters are bitter and windy, you must have a love for those around you who share in the challenges of daily life… and who can enjoy a nice, warm dish of qurutob.

ABOUT THE RECIPE

Make no mistake about it: making a dish like qurutob from scratch is not for the faint of heart. If you’re willing to stick with it, though, we can promise you that it’s one really intriguing and memorable dish.

Part of the reason lies in the components of the dish. There are several distinctive ingredients that, while widely used in many Central Asian cuisines, haven’t quite made their way into Western supermarkets quite yet. As a result, you’ll see that we had to prepare most everything from scratch, including making the dry yogurt.

Yogurt is a common ingredient in many dishes, just not quite so with American dishes. For instance, it is common to have Greek Yogurt as a soup garnishing in dishes like this vegetarian ajiaco. We found it a pleasant to be adding yogurt to our cooking with some of these international dishes at Arousing Appetites, instead of always eating it as a snack or light lunch like we normally do in America.

QURUT: DRIED YOGURT CURD

We’ll start with qurut, which lends its namesake to the greater qurutob. Much like the jameed we saw in Jordanian mansaf and kashk in Persian cuisine, qurut is a ball of fermented milk or yogurt curd that has been dried out to remove excess liquid and whey. If bought pre-made, you’ll find that qurut comes hard in texture but is easy to crumb, particularly in the presence of liquids.

For those that can’t find qurut easily, you’re in luck. It’s actually fairly easy to make, but it does take a bit of time. All it takes, though, is to bake some yogurt dry.

FATIR: SWIRLED FLATBREAD

While the qurut is fairly easy, its breaded qurutob counterpart fatir requires a little more finesse. Fatir is a traditional Tajik flatbread which, in our case here, will be torn up and added to a thicker qurut-based sauce.

To prepare fatir requires several different steps. First comes creating the dough itself, which then gets flattened and cut into two identically sized rectangular pieces. On the top side of each piece, you’ll either evenly lather softened lamb lard (or, in our case, butter) over top before commencing the rolling.

The key to fatir is making a cylinder out of the dough. Start by rolling one part of the dough into a tight cylinder, and you’ll follow by rolling the other piece of dough around it to create an even bigger cylinder.

Finally, you’ll press it firmly down to create a flat circle of swirled dough and fat, a mixture which will bake evenly and beautifully in the oven for at least half an hour.

MARINATED ROASTED LAMB

The final piece of the qurutob puzzle is the lamb. Some suggest cooking a lamb shank, but regardless of what cut you use, it’s not unlike other preparations of lamb. You’ll marinade it in some oil and spices like cumin, coriander and chili powder, followed by searing and baking it until it’s cooked through.

When it does cook in the oven, however, you’ll add some chopped tomatoes into your pot or Dutch oven to help create a pseudo-stock from the composite lamb and tomato juices. This proves to be a big driver of the flavor behind qurutob.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Once you have the fatir, qurut and lamb shank squared away, actually creating your qurutob isn’t that hard. You’ll start by sautéing and frying onions until golden brown, then you’ll add in your qurut and some of the “pseudo-stock” to create a thickened, somewhat lumpy mixture. The lamb will go into this sauce to absorb more flavors along with the its accompanying roasted tomatoes.

Here you’ll add in your torn pieces of fatir and stir around to get them nice and covered with the sauce. And then you’re done!

OUR TAKE ON THE RECIPE

It doesn’t take too much sleuthing to discover that coverage on Tajik cuisine isn’t very extensive. There are perhaps a handful of books you can find on Google or elsewhere, but the range of potential source recipes for qurutob was very, very limited.

Still, we came across one that had both an excellent dissection of qurutob and its separate components, and so we used it as a reference for our own to go from there. Of course, we made our own adjustments along the way.

Perhaps the greatest adjustment we made was with the lamb. Our cut of choice for this recipe was a bone-in lamb shoulder instead of a shank. And instead of an oil-based marinade, we created a dry rub that went directly onto the lamb before searing. Without any oil, we significantly upped the proportions of the rub too, a move that in our minds yielded a more flavorful, fragrant residual stock. As for the fatir and qurut, any adjustments we tried didn’t yield a better result, so we worked with the recipe as is.

While not necessarily an adjustment in ingredients, we also readjusted the recipe to better handle the multiple phases in parallel instead of sequentially. This way, preparing qurutob isn’t so much of an all day affair but rather one of a few unique hours.

In the end, qurutob is certainly one of the most unique and special dishes we have made so far in our pursuit to cook the world, and it’s most definitely worth trying.

Enjoy!

How would you approach preparing qurutob? Comment below!